What Are the Different Cuts of Beef?

The Basics: Primal vs. Subprimal and Food Service Cuts

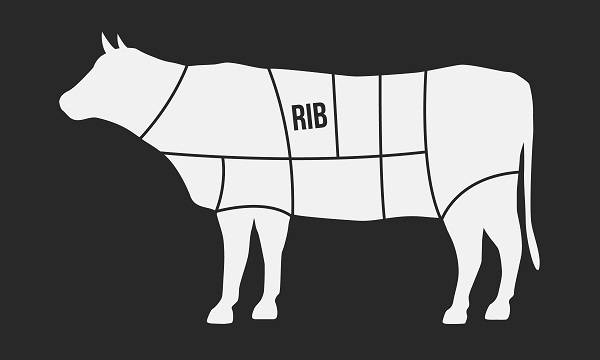

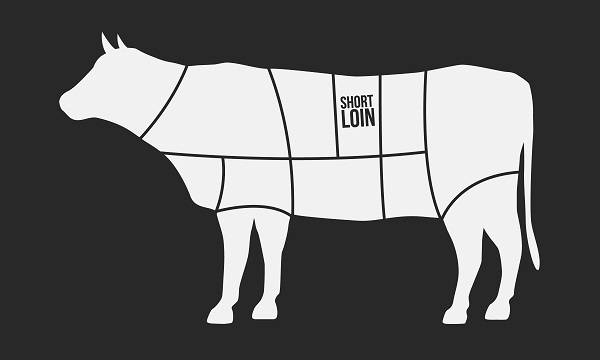

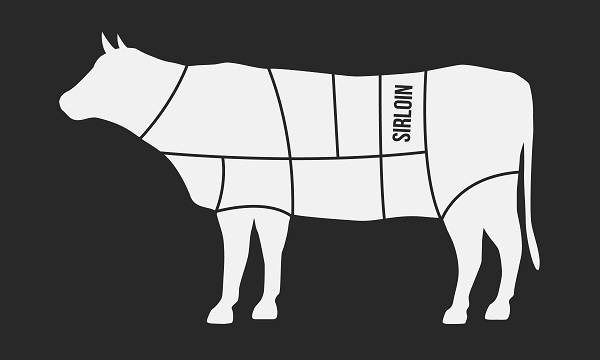

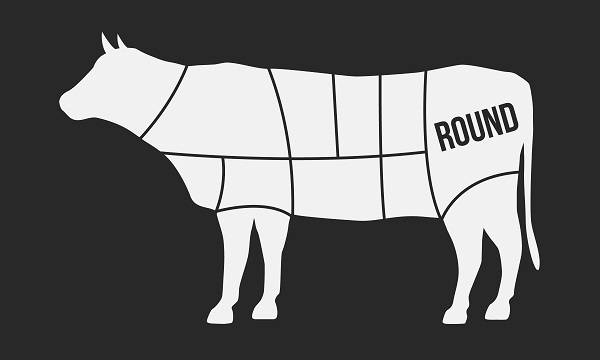

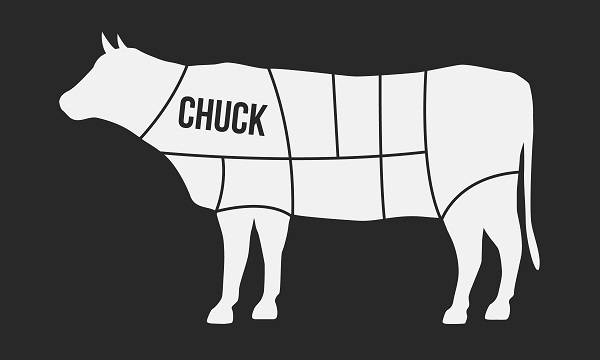

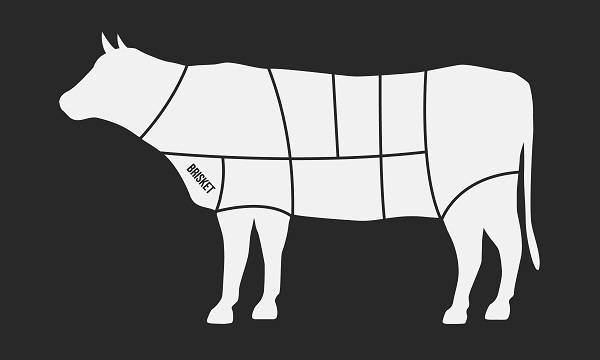

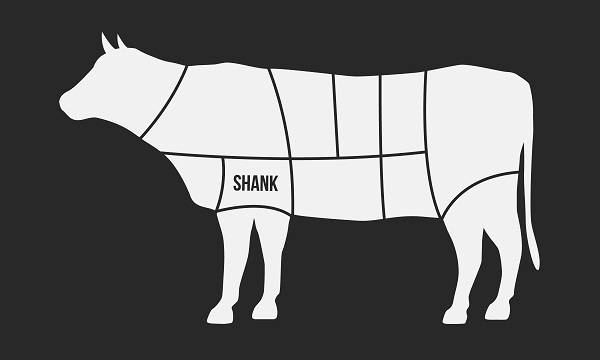

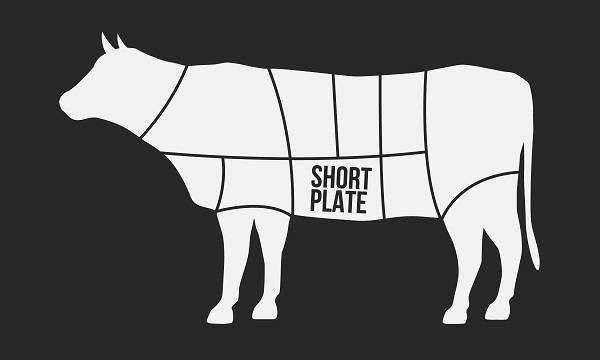

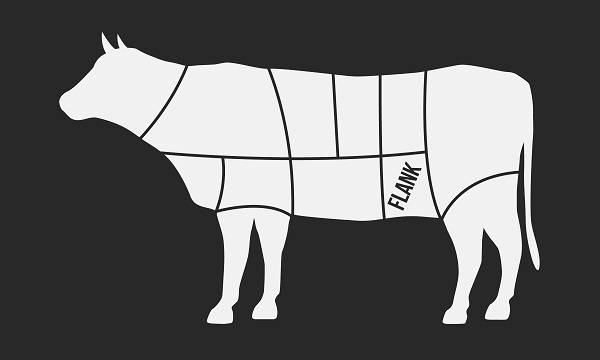

Here’s the rub: When butchers receive a whole cow, they first break it down into eight to 10 large sections called primal cuts. Names such as chuck, rib, loin, and rump all fall into this category. From there, primal cuts are broken down into subprimal cuts, or smaller pieces from each primal cut. But what you find in a butcher shop or your grocer’s meat aisle are much smaller, more specific cuts called food service cuts. These cuts are fabricated into skillet-ready (or grill- or oven-ready) steaks (think T-bone), roasts (such as standing rib roast), and other retail offerings (such as short ribs and ground chuck) that you’ll often see in recipes. To put it into perspective, a 1,000-pound steer yields about 465 pounds of retail cuts. Of those, only 75 pounds are what we would call steaks (such as a T-bone, sirloin, or porterhouse).

But how do you know which cut of meat works well in what recipe? As a general rule, certain cuts of steak are best grilled, while others are tastier roasted, and still others are best pan-fried. Thrifty cuts, from the ends and underside of a steer, do better braised at low heat.

Here’s a shallow dive into the primal cuts—and which retail cuts come from each, with hints for what parts of the animal fare best with specific cooking methods for the most flavorful, tender result.

The 9 Primal Cuts